The German Colonies on the Volga

Bishop Kessler 1922

From the front page of the Ellis County News - Thursday, February 9, 1922 - Bishop Kessler Spoke at Hays

Points from Bishop Kessler's speech Sunday afternoon at the Knights of Columbus Hall

NOTE: (Bishop Kessler was from the home town of Charles & Anthony Rigelhof and was the parish priest at the time before he became bishop)

During the 1760s, 104 German colonies were founded on the unsettled Russian steppe near the city of Saratov on the Volga River. Approximately 30,000 colonists primarily from the Hesse and Palatinate areas of present day Germany were encouraged to colonize Russia by Catherine the Great.

These pioneers shared a rich life based in German culture, language, traditions and religion but influenced by their Russian neighbors and environment.

Today, those born on the Volga and their descendants are scattered in many parts of the world including Canada, the United States, Germany, Argentina, Brazil, South Africa as well as those who remain in European Russia, Kazakhstan, and Siberia.

Bishop Joseph Kessler of the Sea of Tiraspol, Russia, spoke last Sunday afternoon at the Knights of Columbus Hall, in which he gives a review of the history of the last seven years in Russia, the events leading up to the revolution, then the breaking down of the revolutionary forces into the Bolshevik regime, the civil war that took place in the German colonies of the Volga region, and the story of dire distress and the devastation that it all occasioned. The Bishop spoke in German and the following paragraphs were supplied us by one who made as full long hand notes as possible during the speech. Among other things the Bishop said: The cause of the fall or the Russian government, that is, the old Czarist government was not the German and Austrian armies, but was due to the irreligion of the ruling class. A People under a government where there is no justice become a great band of robbers. So it was the injustice against the people by the Czarist government that caused the fall of that government and of all Russia itself. The German people in Russia (the people of the Volga region) were constantly referred to by the ruling Russian people as the deaf-mutes (Stummen) meaning that they had no part in the government and had nothing to do with its workings, and the ruling government came to consider that these people had no rights that should be respected. The Bishop said: "I myself was sent to Petrograd to intercede for the Germans of the Volga region, but without avail."

The German people in Russia have always had great dread of war of any kind, and especially of war between Russia and Germany because in this kind of war they saw great disadvantage at which they would be placed. In a sense they were orphans in a foreign land, with no paternal protection, that is, government protection. They couldn't appeal to Russia nor could they appeal to Germany.

On February 26, 1917 there was an order sent out by the Czar demanding of the 2,000,000 German people in Russia, all of their grain and goods and cattle and horses, that they had in their possession. Upon the fall of the Czarist government it was found that this order was planned by the Czarist government with the view to starving and driving all of the German subjects out of the dominion of Russia. At the time of the fall of the Czarist government, orders were in the hands of the army to proceed with forces into the colonies along the Volga to execute this commandeering ukase. On that same day, I had urged the boys in my Seminary of Saratov (because there were no men except old men at home) to pray for a miracle to save us from extinction, and on the same day, the revolution began in Petrograd, 1800 mounted Cossacks were held in readiness at Saratov, to swoop down on the defenseless villages, to murder, plunder and scatter the inhabitants. But on account of the revolution the order was never executed. This gave us new hope for a time.

The common people of Russia longed for peace. Kerensky, the leader of the revolutionists, was for peace as long as the old regime was in power, but as soon as he secured control, he said: "cursed be all those who want peace". Now we're the bosses". Kerensky himself went to the front to encourage the soldiers to go on, but to no avail, for he didn't have power to control so many million soldiers. Lenin, who headed the Socialists in Russia, came forward with promises of peace to all. He promised the people land for which every farmer in Russia had longed for and hoped for. The people believed that the government could make them rich in land if it but wished. As a matter of fact, if all the available land had been equally divided it would have given each but 2 1/2 hectares. Lenin told the people in a speech that they should rob those who had robbed them, that is, they should rob the rich, and by that time the people were in such a frame of mind that it didn't that much urging to get them to act upon this suggestion at once , and instead of laying down their arms they came home and began to carry out Lenin's suggestions. That's where the folk- warfare or civil war began. Every night many murders of the rich were committed by the Bolsheviks and the returned soldiers. Our diocese was robbed of one fourth million gold rubles, which we had accumulated for a new seminary. About that time the Bolshevists began issuing mandates. The first was that all who had 25,000 rubles or more should have the entire sum commandeered by the Soviet government (at this time the ruble was worth about one-half of its full value). This was a sample of the Bolshevist paradise which they had promised the common people. This 25,000 ruble limit was reduced by new mandates until it got so that they took anything which anybody had from him, on the theory that all should be alike. Why did they take all this property? Well, when you take all that a person has you make him your slave. This system resulted in terrible tyranny and terrible slavery. People cannot be made into animals by a government, which was what the Bolshevist government tried to do . The people took up arms against it and a war of reason against slavery was on. The Bolshevists made their army discipline effective by extreme cruelty.

Many, almost every offense was punishable by death. The Bolshevist soldier was well paid and his family were well provided for. As a sample of discipline the Bishop told how a Bolshevist soldier asked his officer for pay, and was led by the officer into the back yard and was shot down. "People became so used to murder that it made no impression at all upon them.

The communists required that all who had less than 25,000 rubles of wealth must turn it all over to the common fund. This practically ruined our farmers, for it took even their seed wheat. In every community there was a local man, a communist, if one could be found who could be trusted, and if such a local communist could not be found then someone was sent in from the outside to take charge of every village and he was furnished with sufficient soldiers to prosecute the execution of his order.

Concerning myself I will say that I was urged by priests and friends to leave Saratov because I had been sentenced to death by the Bolshevists, and I finally went to Odessa in 1918, the largest city in the diocese and then in control of the Germans.

From there I went to the Ukraine, thence to Romania, then to Besserabia and finally to Berlin. After the Bishop's arrival in Berlin he began to organization of relief for the Volga sufferers, thousands of whom, like himself, had drifted back into Germany, and other thousands of whom were detained at the border of Poland, and still other thousands left in Russia, unable to leave or not knowing whether to take the chance of leaving or whether to stay in Russia. He and father Nikelaus Meier had come to the United States to gather funds for the relief of the Volga region, both Catholic and Protestant. They met with a generous response at Hays last Sunday, the subscription for the day amounting to practically $1000. Meetings are being held this week at various towns throughout the country, and will be continued for some time until every one who desires to assist has had an opportunity.

Jacob Dietz

Dietz was first and foremost an advocate and a politician, not a villager, so he wrote his history with the analytical mind of a lawyer. His reports on the Khirghiz raids and Pugachev rebellion are by far the best reports I have read, giving a detailed, blow- by-blow account of the gory battles fought...and it is not for sensitive readers.

Dietz was a man who in his line of duty as an advocated travelled through the German Volga villages, and while attending to the legal aspect of his business, also took copious notes from the old-timers, lamenting that so much history was being lost by the villagers, who were not recording their own lives, partly to the lack of adequate literacy. Interestingly, the first generation of Germans who arrived on the Volga were better educated and more literate so left a trail of documentary evidence of their hardships, while later generations - now leading a fully agrarian existence - had poor access to education and literacy regressed.

As a politician Dietz was elected to the Duma (Russian parliament) and when not sitting in parliament, he was sitting in prison for his left-wing liberal proclamations, but nevertheless much beloved by his GR communities.

In brief, he was the new breed of German colonists who were leaving their villages to emerge as the newly-fledged middle-class of professionals:

JACOB Georgevich DIETZ (son of Georg): 1864 - 1917

- Advocate, Editor of the Kamyshin district newspaper (where he lived permanently, but travel took him throughout the Saratov province frequently)

- Deputy to the 1st Duma for the Saratov Province

- Left-(wing) Cadet and Trud-(Labour)-Party member

- Historian of the Volga-Germans

After higher law education, he left for the Don Cossack territory where he worked for 20 years as an advocate, where he built up a law-practice where he was known as a very "fair" man representing the minorities living in the Ukraine. Later in 1905 he accepted the post as the Saratov Province's advocate to the district court of Kamyshin. From 1906, as editor of the "Volga Region" he travelled frequently from Kamyshin to Saratov city through the German villages, which gave him material for a series of features.

He began to interview the very old people and to record their life's recollections and stories told to them as children by the early settlers. He assembled old letters, biographies and diaries left behind by the original colonists and their children, but these documents have disappeared long ago, so today we are fortunate enough to be able to read his book.

He interviewed grandchildren of the survivors of the Pugachev Rebellion and the raids by the Khirghiz, who took colonists into slavery, selling some as far afield as Samarkand and unto Persia. Dietz did not shrink from the grizzly details and high drama, but told in a measured voice.

We learn that some colonist slaves managed to turn events to their own advantage becoming wealthy and important eastern traders, while others whom fate favoured less, endured a life of cruel destitution and martyrdom. Some returned many years later to their home villages, while others were ransomed.

Dietz wrote this history between 1914-1917 to coincide with the 150-year anniversary of the founding of the Volga German colonies. Short extracts were printed in the "Saratov List", but the full book could not be printed due to the WW1, resultant anti-German sentiment, followed by the revolution and subsequently the civil war.

He died in August 1917 still toiling over his manuscript and it was only in 1926 when his and daughter handed over his work to Engles Archives, where it lay lost and forgotten for 80 years, until its discovery under a loft roof. In 1997 it finally emerges into the world, edited by E. Erina and I. Pleve, and published by the Goettinger Arbeitskreis in conjunction with the International Society of German Culture, the Engels Archives and Gotika Moscow.

As in all such cases, the disadvantage to the modern reader is that many statements are made without explanations, because the author was writing for a specific readership in the early 1900s that was well acquainted with the nuances, details and laws under discussion. His reading public would have had a basic understanding of the subject matter discussed, which the modern reader no longer has.

Unlike the outlook of the clergymen who wrote GR history or the more emotional historians, this lawyer took a cool look at the changing legal landscape, and, unlike his contemporaries, he did not bemoan the passage of time that revoked the Special Colonial Laws in the early 1870s that had been reserved for this minority of German farmers, but, in fact, he welcomed the new equality.

He wrote, contrary to the stable diet most American GRs have been reading, that the average Volga-Germans enthusiastically welcomed the new laws which, though stripping them of certain privileges, nevertheless offered them true equality as fully- fledged Russian citizens - albeit with the addition of compulsory military service.

Dietz believed that the new responsibilities were a small price to pay for the new laws of equality which would bring a new dawn of opportunities to the insular German colonist.

Revoking privileges along with russification and a military call-up was exchanged for a greater personal freedom with permission to leave the villages, private land ownership, start trading unhindered, joint merchants guilds and expand new horizons. It was in this period that the great Volga-German industrialists laid their first foundations for international trading houses.

According to Dietz, the colonial privileges had largely outlived their usefulness. Old privileges become useless, if not a burden for the development of a population group. The invitation to become full Russian subjects held vast advantages for those who were chomping at their bit and beginning to feel claustrophobic in the closed villages.

When the government administrators arrived in Volga-German villages to explain the new laws, they were met either with enthusiasm or mute compliance or a mixture of both. None exhibited open antagonism. Many celebrated .... so according to Dietz, the lawyer.

Many colonists felt this was the new dawn for them to move on and upwards with new responsibilities and new privileges, though Dietz did not spell them out, as he wrote in Russian for a his contemporaries who would have readily understood the detailed picture.

It is interesting to observe, that this was also the period when colonists preferred to use their new-found freedom to leave Russian altogether for the Americas, but, they were in the minority.

Lawyer Jacob Dietz was a socialist politician and elected member of the Duma, even though he was born into a typical colony-village. Embracing russificiation allowed him a brilliant career path.

The new freedoms led to an exodus of Germans out of villages - not only to America and Siberia as new colonists and settlers - but also into towns, where they founded their own trading houses, mills, distilleries, wagon-making, manufacturing farming equipment, cement works, leather-dying, chocolate and sweets factories, tanneries, inns, hotels, river boat and eventually shipping lines.

Later, as land became scarce, the young who did not migrate to the Americas or Siberia or Kazakhstan, moved to towns as the new blue-collar working-class to take up jobs in the German mills and factories, as German industrialists preferred employing their "own" Volk wherever possible: same language, same culture, same work ethics. Many were related, and the poor cousins moved up to the rich uncle's firm - not only as worker's - but also as white-collar clerks, shop assistants, stewards, book-keepers, secretaries, governesses and teachers.

Not all historians, of course, shared Dietz's enthusiasm for the New Laws, and one can read "The Acquiescence of many Germans to the Russianization program" by Dietmar Neutatz. The term 'acquiescence' infers a type of grudging, passive compliance, yet most Volga-Germans reacted relatively calmly to the Russianization program, recognizing that being forced to learn Russian was at least partly understandable and might even be advantageous.

Arrival in Russia

From 1764 to 1772, 30,623 colonists arrived in Russia to start new lives on the Russian steppe. Most of the families came from German speaking lands although a small number of people came from other parts of Europe such as England and the Scandinavian countries.

As soon as the would-be emigrants had signed their immigration contracts and arranged their affairs, they were assembled in a few centrally located cities, where the Russian agents found them temporary living quarters and gave them daily allowances for food. When sufficiently large numbers had been assembled, they were transported to one of the Baltic ports, usually Luebeck from where Hanseatic or English ships took them east across the Baltic Sea into the Gulf of Finland to Kronstadt, near St. Petersburg. Luebeck was an especially busy point of immigration with over 72 percent of the colonists leaving for Russia sailing from this port in 1766 alone.

The 900 mile voyage by ship from Germany to Russia could normally be made in 9 days. Inclement weather and unfavorable winds could prolong the journey to several weeks. Sometimes dishonest ship captains would delay which allowed them to see provisions at inflated prices as the colonists supplies diminished. In one case, the journey from Luebeck to Russia lasted three months.

Many left their homes to escape a war-ravaged Central Europe that had suffered socio-economic devastation wrought by the Seven Year's War which ended in 1763.

Recruiters under the employ of Catherine II (Catherine the Great) were sent to many areas of Central Europe with her Manifesto which invited people to migrate to Russia.

By 1798, there were more than 38,800 individuals living in 101 German speaking colonies along the Volga River near Saratov.

Immigrants traveling from the German lands would first arrive at Kronstadt, a Russian naval Port located on a island in the Gulf of Finland west of St. Petersburg.

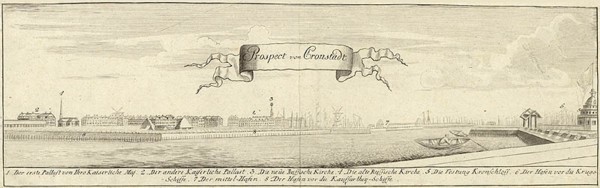

A view of the south side of Kronstadt from the l,800s.

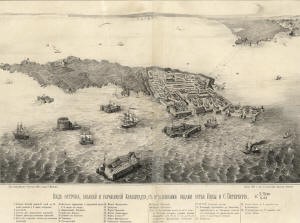

A birds eye view of Kronstadt from 1855.

Ships near the Kronstadt fortress in 1780.

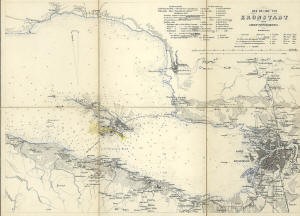

A map showing the island of Kronstadt. St. Petersburg is to the east and Oranienbaum is south of the island.

From Kronstadt, the colonists were taken to the city of Oranienbaum (Lomonosov) on the mainland. Oranienbaum is located near St. Petersburg and was the site of one of Catherine II royal residences known as the Great Palace of Oranienbaum.

Catherine had elected to make her murdered husband's (Peter III) palace her summer residence after his death in 1762. The palace is built near the shore of the Gulf of Finland, just opposite of the island on which Peter the Great had situated the Kronstadt Fortress that protected St. Petersburg. A canal ran from the shore to the palace, making it possible to sail almost to the gates of the lower garden.

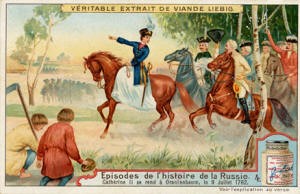

The colonists were often lead in the oath of allegiance to the Russian Crown by the German pastor of the Lutheran Church in Oranienbaum. It is reported that Catherine herself would sometimes welcome the colonists in their native German language from the balcony the Great Palace which faces the Gulf of Finland.

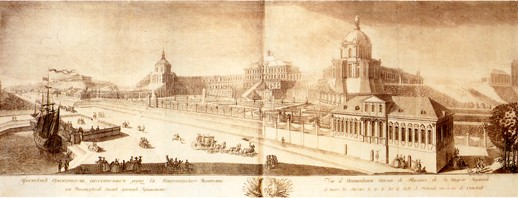

A print by Chelnakov and Knunov after a drawing of the Great Palace in Oranienbaum, Russia by Makhaev. The Great Palace was also known as Catherine II Summer Palace. The drawing shows a sailing ship tied up near the gates to the palace. This is the likely landing spot for the Germans who were arriving in Russia.

The Great Palace in Oranienbaum - Just out of view is the canal linking the gates to the Gulf of Finland

Gates of the Great Palace in Oranienbaum. The canal to the Gulf of Finland can be seen in the background.

From 1766, the reception and housing of the colonist was the responsibility of the Titular Counselor, Ivan Kuhlberg. Kuhlberg also recorded and compiled lists of the colonists as they arrived in Oranienbaum. More than 20,000 persons, or 6,500 families are reflected in the Kuhlberg lists. The lists are compiled by ship, with an indication of the date of arrival in Russia, port of departure, the name of ship, and the name of the captain. The given name and surname of the colonists are listed along with the composition of the family (age of children was indicated), location from which they came, religious confession and place where they desire to settle. From these lists we know a few of the ship names such as The Elephant, Love and Unity and Anna Catharina.

Catherine II in Oranienbaum with Russian peasants looking on

In Oranienbaum, the colonists they were given materials to build huts for their temporary accommodation while they waited for the next move. Arrangements for their accommodation were of the most primitive kind. Colonists remained in Oranienbaum from two weeks to several months making preparations for the long journey to their new homeland.

For the first time, the immigrants saw the general backwardness of Russia. Most disappointing to many of them was the fact that, in spite of the promises that had been made, they were not free to go where they liked in Russia. Many of the colonists intended to pursue their trades near St. Petersburg where there had been a sizeable German community since the time of Peter the Great. Most colonists were compelled by Russian officials to join the majority of the settlers in developing the agricultural lands on the lower Volga River near Saratov. However, some colonists were settled in areas of St. Petersburg, Moscow and Tallin. Other colonists settled in Astrakhan, Sarepta, Ukraine and Estonia.

Several routes were taken to the lower Volga. Not all of the colonists survived the trek to the lower Volga. Of the 26,676 colonists dispatched from Oranienbaum, 3,293 (12.5%) died in route.

Transport lists were compiled as colonists arrived in Saratov by Russian army officers who escorted the transports. In addition to the names of all members of the family and the ages of the children, also births and deaths were listed. These lists were not completely preserved. The years of 1766 and 1767 were covered but the exact dates of each transport are not indicated. There are a total of 7,501 individuals mentioned on the nine transport lists.